Matthew Wheeler of the International Crisis Group (sometimes referred to as ICG or simply, the Crisis Group), recently wrote an editorial in the New York Times titled, “Can Thailand Really Hide a Rebellion?” The editorial took a coercive tone, with its final paragraph appearing almost as a threat, stating:

It would be shortsighted and self-defeating of the generals running Thailand to insist on dismissing these latest attacks as a partisan vendetta unconnected to the conflict in the south. They should recognize the insurgency as a political problem requiring a political solution. That means restoring the rights of freedom of expression and assembly to Thai citizens, engaging in genuine dialogue with militants, and finding ways to devolve power to the region.

Wheeler’s editorial intentionally misleads readers with various distortions and critical omissions, mischaracterising Thailand’s ongoing political crisis almost as if to fan the flames of conflict, not douse them as is the alleged mission of the Crisis Group.

Wheeler’s recommendations to allow violent opposition groups back into the streets for another cycle of deadly clashes (which have nothing to do with the southern insurgency) while “devolving power” to armed insurgents in the deep south appear to be a recipe for encouraging a much larger crisis, not resolving Thailand’s existing problems.

Wheeler never provides evidence linking the bombings to the insurgency or provides any explanation as to why the insurgency, after decades of confining its activities to Thailand’s southern most provinces, would escalate its violence so dramatically. Wheeler also intentionally sidesteps any mention of evidence or facts that indeed indicate a “partisan vendetta.”

Instead, his narrative matches almost verbatim that promoted by the primary suspects behind the bombings, ousted former-Prime Minister Thaksin Shinawatra and his political supporters.

Wheeler’s distortions include an intentional omission of the scale of violence Shinawatra and his followers have carried out in the past, as well as the political significance of the provinces targeted in the recent bombings in connection to Shinawatra’s conflict with the current ruling government, not the insurgency’s,

The provinces targeted represented political strongholds of anti-Shinawatra political leaders and activists, all of whom have no connection at all to the ongoing conflict in Thailand’s deep south.

Crisis Group is Covering up an Engineered Buddhist-Muslim Conflict

More alarming are Wheeler’s attempts to cite growing tensions in Thailand’s northern city of Chiang Mai between Buddhists and Muslims as evidence, he claims, of the real dimensions of Thailand’s conflict. Wheeler is attempting to claim Thailand is experiencing a potential nationwide religious divide, separate from Shinawatra’s struggle to seize back power.

However, he cites a 2015 protest with a decidedly bigoted tone targeting a Halal industrial estate that was slated to be built in the northern city. The protest was led by monks affiliated with Thaksin Shinawatra’s political movement, including monks whose temples Shinawatra’s family visits regularly, including Sri Boonruang Temple whose walls are adorned with images of Thaksin Shinawatra himself.

These temples and those who frequent them represent a divergent and politicised version of Buddhism, Buddhist in name only.

They are actively involved in directly supporting Thaksin Shinawatra and working along political peripheries to divide and destabilise Thai institutions and sociopolitical balance impeding Shinawatra’s return to power.

The anti-Muslim protests appear almost identical to anti-gay protests staged by overt supporters of Thaksin Shinawatra, a group called Rak Chiang Mai 51. Out in Perth, a gay news service based in Australia, would report in its 2009 article, “Chiang Mai Pride Shut Down by Protests as Police Watch On,” that:

Organisers were forced to call off Chiang Mai’s planned second annual Gay Pride Parade on February 21 after harassment from the Rak Chiang Mai 51 political group. Dressed in their trademark red shirts, members of Rak Chiang Mai 51 locked parade participants into the compound where they were gathering, throwing fruit and rocks and yelling abuse through megaphones.

In an interview with Rak Chiang Mai 51 leader Kanyapak Maneejak (also known as DJ Aom), when asked about the incident during a “City Life Chiang Mai” interview, she claimed:

Our third aim is to protect Lanna culture and we simply did not like the Gay Pride Parade. In the past there were no gays or ladyboys, but today they live together openly, they wear revealing clothes in the streets. We had to go out in force to protect our culture against this. The people who were spitting were not red shirts; they were infiltrators who wanted us to look bad. It was not just us who wanted to stop this parade, villagers and the entire province of Chiang Mai called up our station to ask us to intervene. We were afraid that this would become an annual event, and we all know that Chiang Mai is a place for human trafficking.

The bizarre defence of the group’s violence and intolerance predicated on defending “Lanna culture” echo verbatim the rhetoric now being directed at Muslims by groups also centred in Chiang Mai.

Both Chiang Mai’s Muslim and gay communities have noted this sudden and unprecedented intolerance and violence has taken them by surprise, as it has many Thais across the country and those familiar with Thailand’s renowned culture of tolerance and inclusion.

The most extreme among politically motivated Buddhist sects have even taken to the streets in protests similar to those carried out by politicised sects in neighbouring Myanmar. In Myanmar, such protests are staged both in support of Aung San Suu Kyi’s National League for Democracy and as part of a violent campaign against Myanmar’s Rohingya minority.

So similar are these two political movements that the Western media has found itself once again playing a role intentionally deepening sociopolitical, ethnic and religious divides.

Reuters in a 2015 article titled, “Spurred by Myanmar radicals, Thai Buddhists push for state religion status,” would claim:

A campaign to enshrine Buddhism as Thailand’s state religion has been galvanized by a radical Buddhist movement in neighboring Myanmar that is accused of stoking religious tension, the leader of the Thai bid said.Experts say the campaign could appeal to Thailand’s military junta, which is struggling for popularity 18 months after staging a coup, and tap into growing anti-Muslim sentiment in a country that prides itself on religious tolerance.

Reuters’ report is a distortion, however. It claims that the military-led interim government might find the idea of dividing Thailand along religious lines appealing, but it is the government itself that is attempting to promote an inclusive society and prevent sociopolitical, ethnic and religious divisions.

It is particularly interesting to note how not only Reuters, but also foreign-funded organisations posing as nongovernmental organisations (NGOs) in Thailand are attempting to blame the government and Thailand’s institutions for growing bigotry and calls for violence toward Muslims despite the fact that the worst offenders are centred around Shinawatra’s political strongholds in northern and northeastern Thailand, precisely where overt supporters of Shinawatra have already put their bigotry and violence on full display.

The government for its part, has both condemned such bigotry, and has taken tangible action to combat it. The Tourism Authority of Thailand (TAT) would publish in its news feed a report titled, “Thailand’s Muslim-Friendly Destination Strategy Goes Well Beyond Just Tourism” (PDF), which aptly quantifies the current government’s position on the subject, stating (our emphasis):

When one of Southeast Asia’s largest Buddhist-majority countries launches a tourism outreach to attract Muslim visitors, it clearly has a much wider significance than just a travel industry development. Although the primary goal of the tourism authorities is to boost visitor arrivals, expenditure and average length of stay, the Thai government is also mindful of the broader goal to build inclusive societies, prevent religious and ethnic conflict, and contribute to the third and, arguably, the most important pillar of ASEAN integration, the Socio-Cultural Blueprint.

And similar comments, sentiments and initiatives can be found throughout the interim government’s activities since taking power in 2014. The Reuters report, like the Crisis Group’s NYT editorial penned by Matthew Wheeler, is merely an attempt to create and compound conflict, not inform people of its true characteristics, nor defuse it.

Anti-Islamic Violence in the North, Anti-Buddhist Violence in the South, Meeting in the Middle

A Thai-based Buddhist scholar when interviewed, helped make sense of the networks of politicised Buddhism attempting to divide Thailand religiously; stating:

The anti-Halal and anti-Muslim movements involve a faction of people connected to the [pro-Shinawatra] Reds… there is an anti-Islamic sentiment within their Buddhist-faction. One person who I know is involved with the anti-Islam group is a professor, Banjob Bannaruji — he is the face for them. He is very popular with Mahachulalongkornrajavidyalaya University.

Banjob Bannaruji would also be mentioned in the above cited Reuters article as leading the campaign to push Buddhism as Thailand’s “state religion.” It should be noted that both in 2007 and again in 2014 his attempts to push this agenda have been rejected by charter drafters, the military and now two interim governments.

While extremist sects in northern Thailand, considered strongholds of Shinawatra’s political influence, are taking on a violent stance toward Islam, there is evidence that Shinawatra has also deployed agitators to Thailand’s deep south to stir up instability there.

A classified 2009 US diplomatic cable titled, “Southern Violence: Midday Bomb Attack in Narathiwat August 25 Meant to Send a Signal,” released by Wikileaks, reveals that the US Embassy maintained contacts with militants in the deep south, claiming (our emphasis):

Insurgents did confirm to a close embassy contact late August 25 that they had carried out the attack, intended as a signal for Buddhists to leave the deep south. With local elections scheduled for September 6 and a string of election-related acts of violence occurring in recent weeks, however, not all deep south violence is automatically insurgency related.

The cable would reveal that Sunai Phasuk, of foreign-funded Human Rights Watch, is their “contact” who regularly speaks with militants.

The US Embassy then admits that Shinawatra’s political forces are also likely operating in the south, using the conflict as cover:

The posting of the anti-Queen banners on her birthday, a national holiday, was both unusual and significant, but the fact that the banners were professionally printed on vinyl, written in perfect central Thai rather than the local Malay dialect, and touched on issues which don’t resonate in the south suggests those behind it were not local but national actors. Most in the know blame the red-shirts seeking to take advantage of inaction in the mosque attack case to undermine the Queen in particular and the monarchy in general.

The US Embassy cable would also admit (our emphasis):

Yala Vice-Governor Gritsada appeared surprised when we mentioned these banners to him on August 19, but he confirmed that the banners were written in perfect central Thai and mentioned issues that do not resonate down south, like the blue diamond. Gritsada said Pranai Suwannarat, the director of the Southern Border Provinces Administrative Center (SBPAC) had agreed these banners were the likely work of the UDD, not the insurgents. Sunai told us that the widespread presence of the banners indicates the strong organization and funding available to the UDD in Pattani province.

The UDD refers to Thaksin Shinawatra’s street front, the United Front for Democracy Against Dictatorship, also known as “red shirts” and include groups such as Rak Chiang Mai 51 mentioned above.

In essence, Shinawatra, his political supporters and his foreign proponents have created their own artificial conflict with which to consume Thailand’s institutions and sociopolitical balance, nationwide starting in the north and south, and meeting in the middle.

In the north, Shinawatra’s networks have mobilised politicised extremist sects to promote hatred and violence toward Muslims. And in the south, Shinawatra has operatives stirring up political instability, and likely even violence to target Buddhists while simultaneously implicating Muslims.

This is the reality of Thailand’s current conflict, a reality Matthew Wheeler of the International Crisis Group intentionally attempts to distort in an effort to protect this reality from the scrutiny and attention required to prevent it from spiralling further out of control. In essence, The Crisis Group is attempting to spur on and exploit, not prevent a crisis. But why?

What is the Crisis Group and Why is it Trying to Destabilise Thailand?

The Crisis Group claims on its website to be, “an independent organisation working to prevent wars and shape policies that will build a more peaceful world.”

If that were the case, one would expect to see the organisation backed by names synonymous with preventing wars and building a more peaceful world. Instead, the Crisis Group’s own website reveals financial support from organisations and corporations openly engaged in precisely the opposite.

Its various councils include such members as oil giants British Petroleum, Chevron and Shell and lobbying firm Edelman UK.

Edelman’s involvement in the Crisis Group is particularly significant since Thaksin Shinawatra employed Edelman as a lobbyist for several years. During Edelman’s lobbying for Shinawatra, Kenneth Adelman served concurrently as both Thaksin Shinawatra’s representative and as a director at the International Crisis Group.

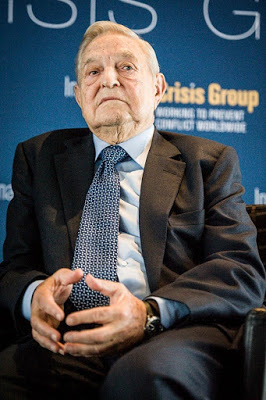

The Crisis Group’s “government and foundation” supporters including USAID and controversial billionaire and convicted financial criminal George Soros’ Open Society. Again, a glaring conflict of interest exists here, with Open Society also funding a raft of organisations posing as NGOs and both foreign and local media working to undermine Thailand’s stability and bring Shinawatra and his supporters back into power.

The implications and actions of the Crisis Group then and now expose the organisation as self-serving merely behind the pretence of “preventing wars and building a more peaceful world.” Then and now, the Crisis Group’s various publications, reports and editorials like Wheeler’s appearing in the NYT have attempted to pressure the Thai government into taking actions that would compound and complicate its ongoing political crisis, not solve it.

In 2010 (PDF), the Crisis Group would urge the Thai government to capitulate to violent street demonstrations staged by Shinawatra which included the deployment of hundreds of heavily armed militants. Nearly 100 were killed in the violence and sections of both the capital Bangkok, and provincial halls across Shinawatra’s north and northeast strongholds were burned to the ground. The Crisis Group’s “recommendations” echoed precisely the demands of Shinawatra himself. Considering that both individual directors of the Crisis Group as well as corporate sponsors were quite literally lobbying for Shinawatra, this should come as no surprise.

What is surprising is that the Crisis Group is portrayed throughout the media as anything other than a lobbying front for special interests, helping to create and exploit crises, not end them.

The New Atlas is a media platform providing geopolitical analysis and op-eds. Follow us on Facebook and Twitter.

Email ThisBlogThis!Share to TwitterShare to FacebookShare to Pinterest