With the victory of Donald Trump during the 2016 US presidential elections, many commentators, analysts and academics have “predicted” a more isolationist America. For Asia specifically, particularly those in need of US intervention to prop up their unpopular, impotent political causes, they fear an ebbing of US support.

However, as history has shown, the whims of US voters rarely has an impact on US foreign policy, particularly amidst the more subtle use of US “soft power.”

US policy toward Asia has been a historical, socioeconomic and military continuum marked by a consistent desire for geopolitical and socioeconomic primacy in the region stretching back for over a century. Since World War 2, the US has attempted to contain a rising China, temper and exploit emerging developing nations across Southeast Asia and prevent nations subjugated to US domination (Japan, South Korea and the Philippines) from achieving anything resembling an independent foreign and domestic policy.

This is a continuum that has transcended presidential administrations and congressional shifts of power for decades.

To believe that the recent victory by Donald Trump amid America’s 2016 presidential election will suddenly change this decades-long continuum is naive and folly.

The networks that primarily seek to establish, protect and expand US primacy in Asia are driven by corporate and financial special interests including banks, the energy industry, defence contractors, agricultural and pharmaceutical giants, the US entertainment industry and media as well as tech giants.

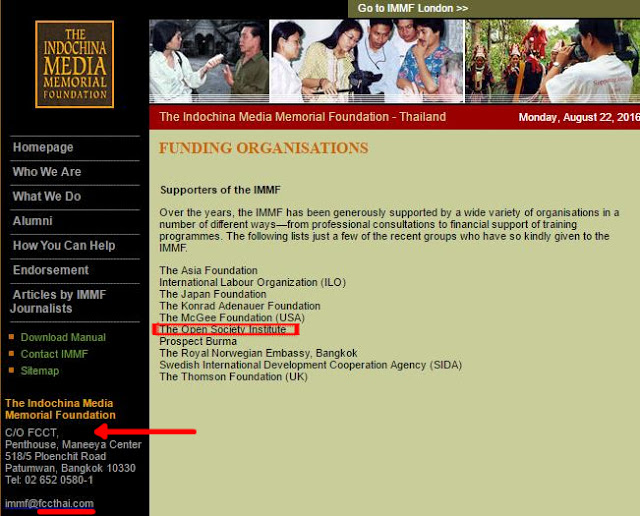

They achieve primacy through a variety of activities ranging from market domination through incremental advances in “free trade,” the funding of academic and activist groups through organisations like the US National Endowment for Democracy (NED), Open Society, Freedom House and USAID as well as direct pressure on the governments of respective Asian states through both overt and covert political, economic and military means.

This is a process that takes place independent of both the White House and the US Congress.

Regardless of how elections turn out, this process will continue so long as the source of these collective special interests’ power remains intact and unopposed.

For Asian states, in the wake of Trump’s victory, keeping track of and dealing with the actual networks used to project American primacy into Asia Pacific is more important than weighing the isolationist rhetoric of president-elect Donald Trump.

Until networks like NED and USAID are either entirely reformed or dismantled, and Asian alternatives are able to permanently displace US economic and institutional domination in the region, the threat of American primacy asserting itself over the interests of Asia itself will persist.

The New Atlas is a media platform providing geopolitical analysis and op-eds. Follow us on Facebook and Twitter.